Big Rembrandt and The Sugar Shack

Ernie Barnes was an author, an album cover artist and perhaps the only player in NFL history who was paid to paint rather than play. Here's his story--from the gridiron to the gallery.

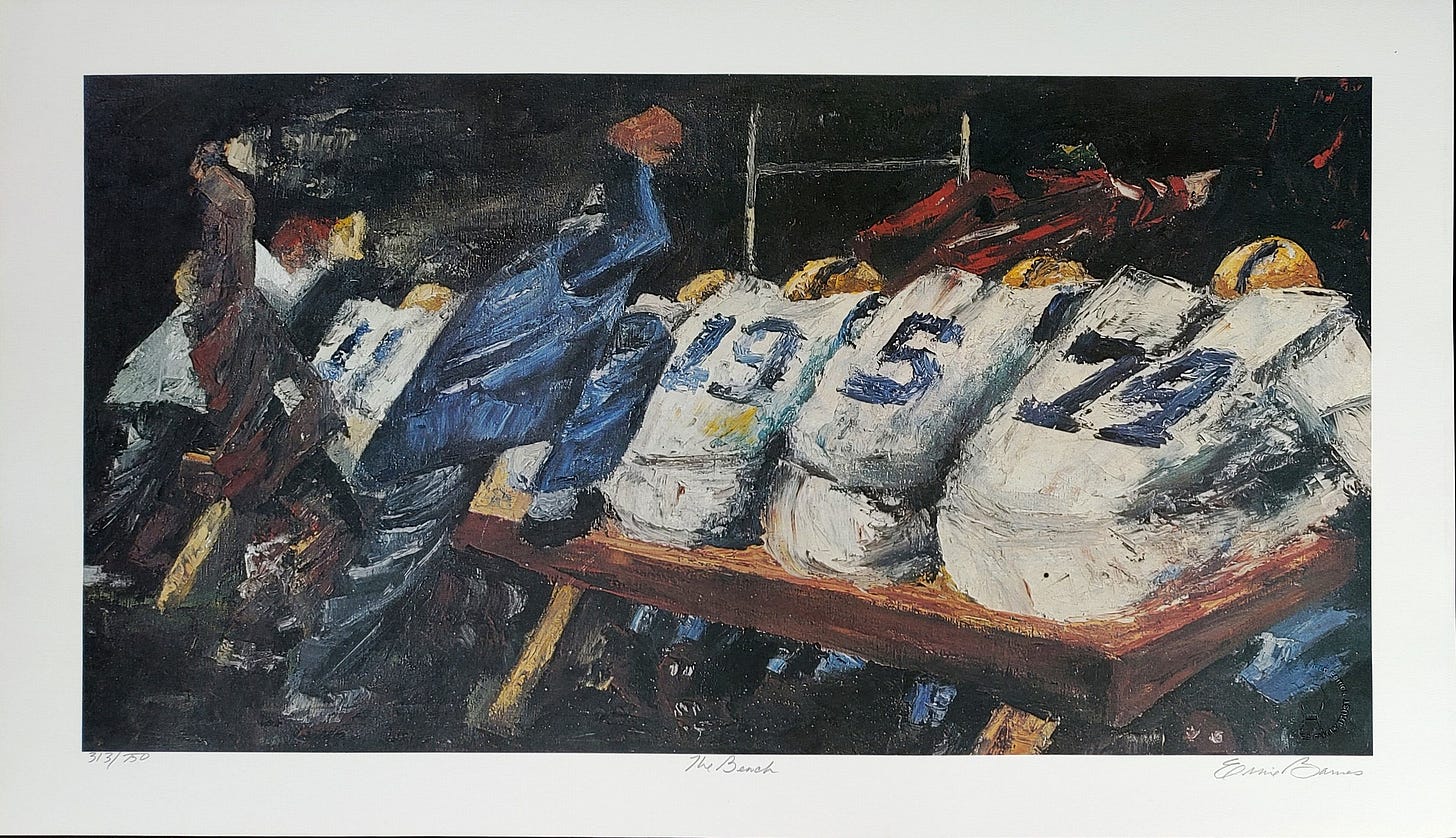

Ernie Barnes was a most remarkable individual–a deeply expressive artist whose work seemed to leap from the canvas with life and sound. He was also a former professional football player, though he was better known during his career for sketching on the sidelines than making the highlight reels.

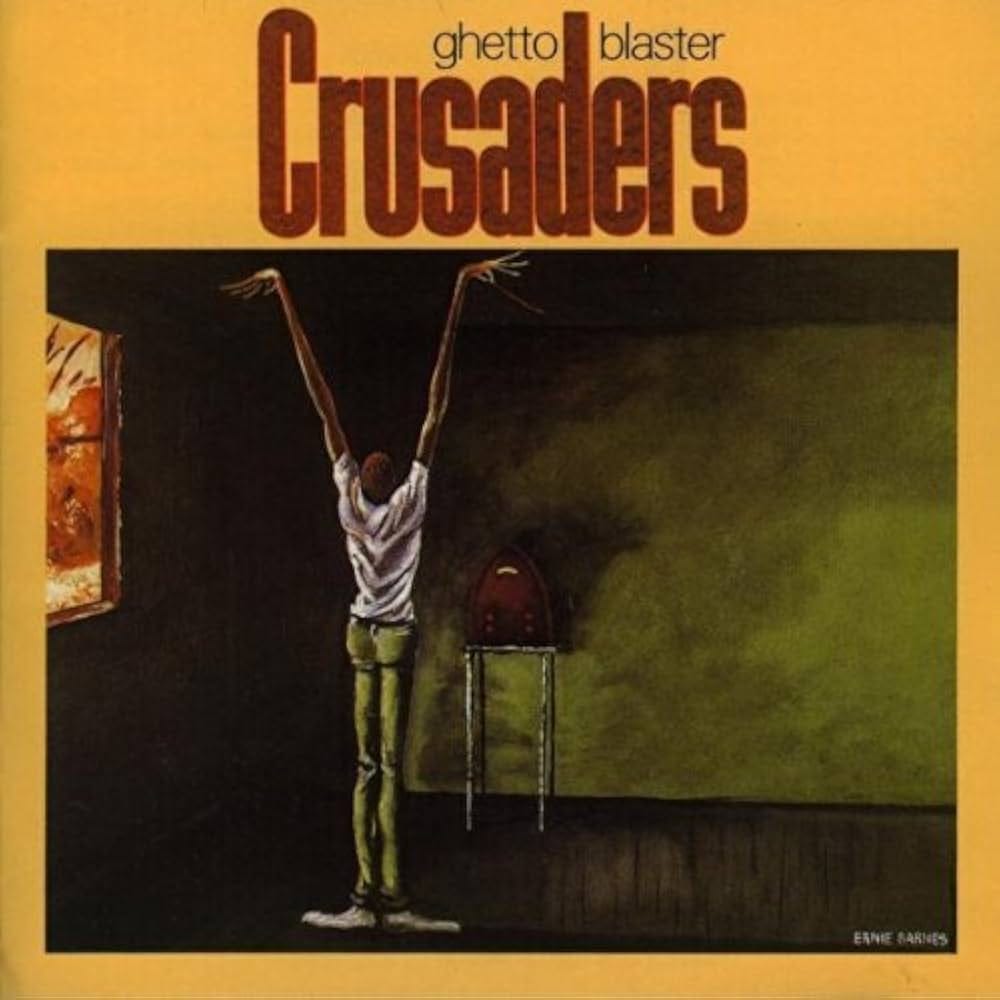

You’ve likely seen some of Ernie’s work, particularly the numerous images that graced album covers in the ‘70s. But it’s possible you didn’t know these were the works of an offensive lineman.

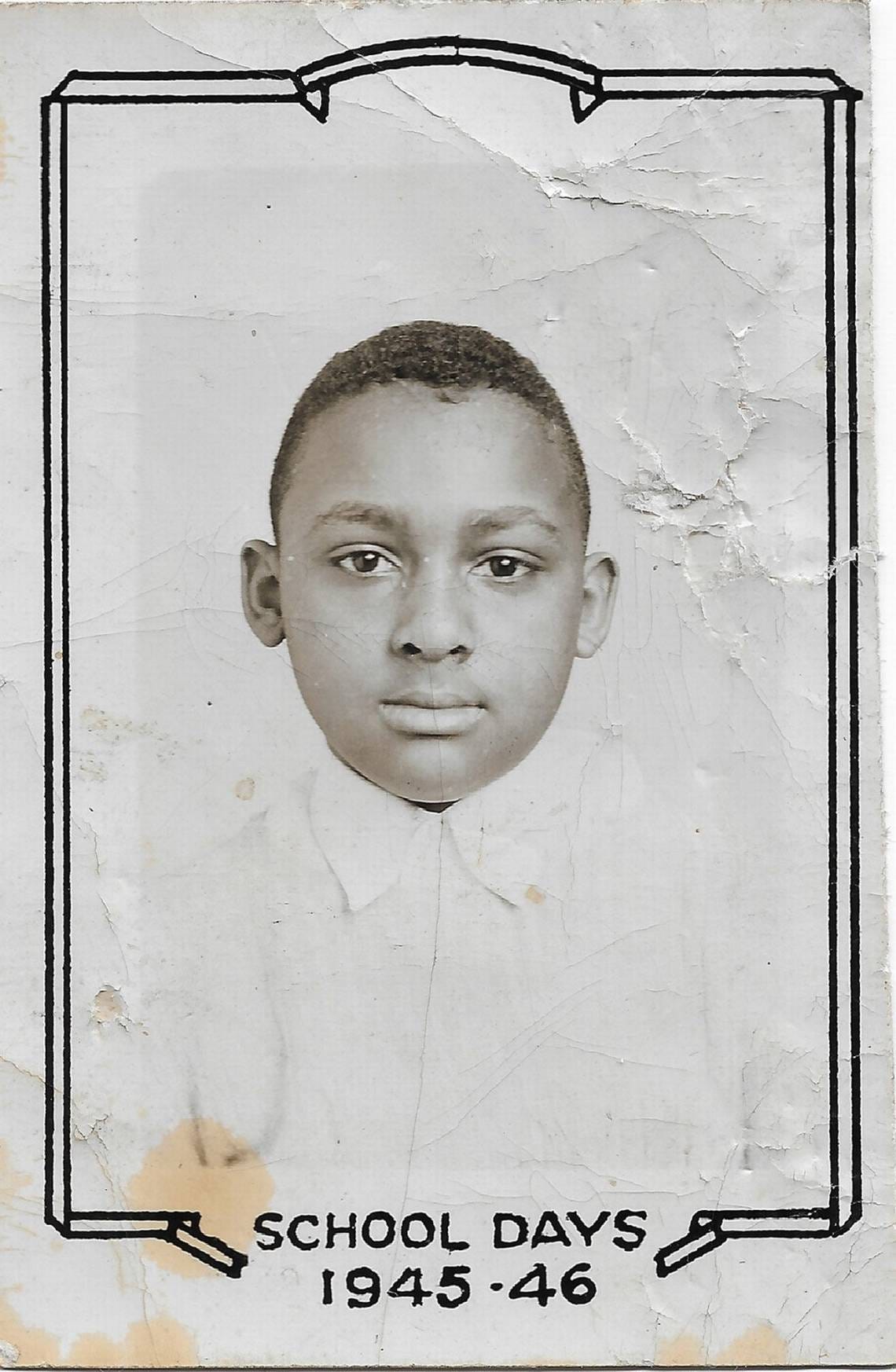

Ernie Barnes was born in Durham, North Carolina in 1938. He was a child of the segregated South. But his mother oversaw the household staff for a prominent Attorney and Board of Education member named Frank L. Fuller Jr.

Fuller truly believed in the value of education, and actively encouraged young Ernie to read books and experience art. These would prove formative experiences for Barnes. As he grew, his sketchbook became a refuge for the shy, chubby kid.

But a chance meeting with a football coach at Hillside High School would change his life.

Intrigued by his emotive sketches, Tommy Tucker told Barnes that weight-training and football had changed his life. Ernie took the advice to heart. By his senior year, he was captain of the high school football team.

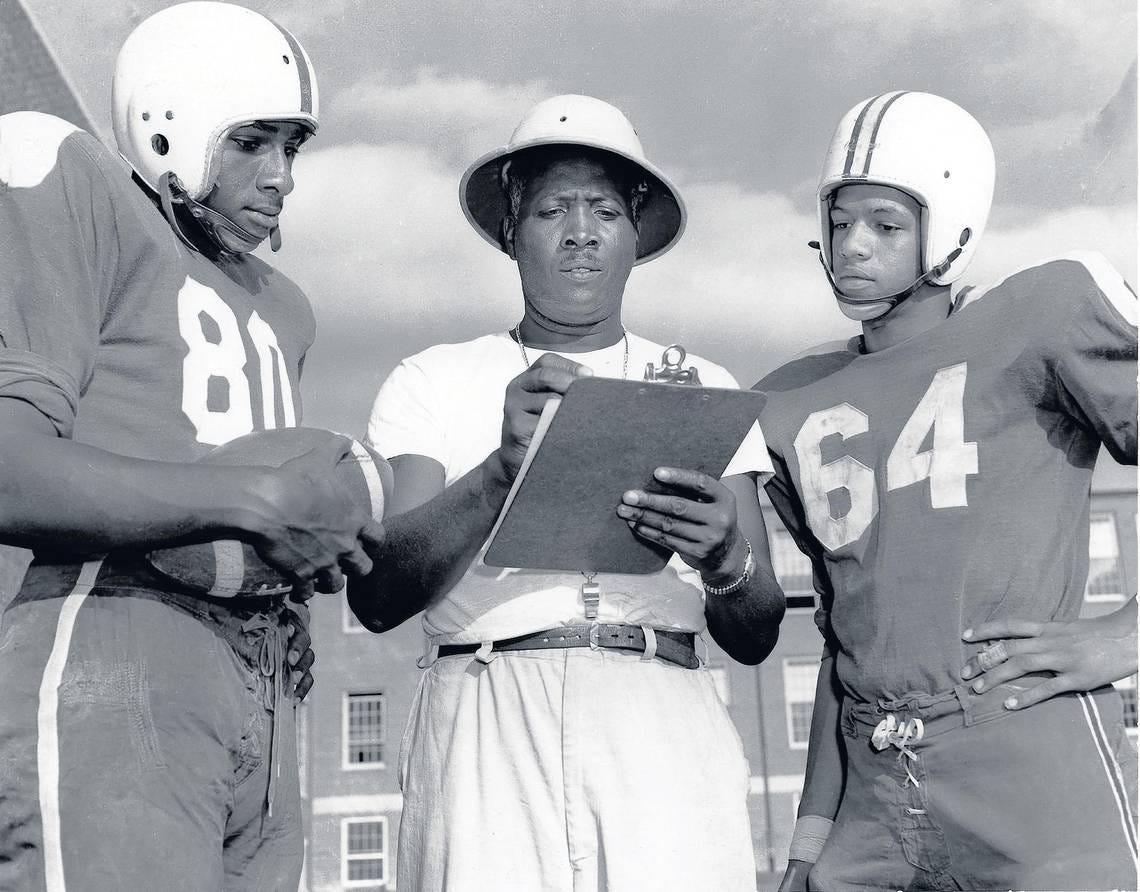

Ernie attended the all-black North Carolina College on a full athletic scholarship and majored in art. That balance would come to define much of his life.

Upon college graduation in 1959, Ernie was drafted in the 8th round by the Washington Redskins. However, when they discovered that Ernie was Black, they renounced their pick. The world-champion Baltimore Colts seized on the opportunity and grabbed Barnes in the 10th round.

Unfortunately, the Colts cut Ernie at the end of the camp and he was scooped up by the brand-spanking new New York Titans. Ernie was less-than-impressed by the organization. He called it a “circus of ineptitude”, observing that “the equipment was poor, the coaches not as knowledgeable as the ones in Baltimore. We were like a group of guys in the neighborhood who said let's pretend we're pros."

(Incidentally, that team became the New York Jets in 1963 and…well…not much has changed.)

When one of Ernie’s teammates–Howard Glenn–died of heatstroke during a practice session, Barnes demanded his release from the Titans. He spent subsequent stints with the San Diego Chargers and the Denver Broncos.

His brief tenure with the Broncos would prove most consequential, owing less to his play than his distinctive artistic ability.

It was in Denver that he earned the nickname Big Rembrandt, both because he shared a birthday with the famous Dutch painter, and because of the way he’d spend his time between plays:

"During a timeout you've got nothing to do – you're not talking – you're just trying to breathe, mostly. Nothing to take out that little pencil and write down what you saw. The shape of the linemen. The body language a defensive lineman would occupy ... his posture ... What I see when you pull. The reaction of the defense to your movement. The awareness of the lines within the movement, the pattern within the lines, the rhythm of movement. A couple of notes to me would denote an action ... an image that I could instantly recreate in my mind. Some of those notes have been made into paintings. Quite a few, really."

By 1965, Ernie Barnes had played his last game–an exhibition match for the Saskatchewan Roughriders in which he fractured his right foot. The following year, Jets owner Sonny Werblin told Barnes that he had greater value to the country as an artist than as a player. It was then that he took a most unusual position as a salaried player whose job was to paint.

Werblin helped to arrange his debut exhibition in 1966 and invited a few prominent art critics to attend. The showing was a sensation.

In addition to establishing Barnes as the most consequential sports illustrator of his time, the succeeding years made him a premier album cover artist as well.

Among his most famous and celebrated pieces was a 1971 painting called The Sugar Shack.

The image first rose to mainstream prominence in 1974 as a still-frame during the closing credits of groundbreaking primetime sitcom Good Times. Two years later, Marvin Gaye borrowed it for the cover of perhaps his funkiest record, I Want You.

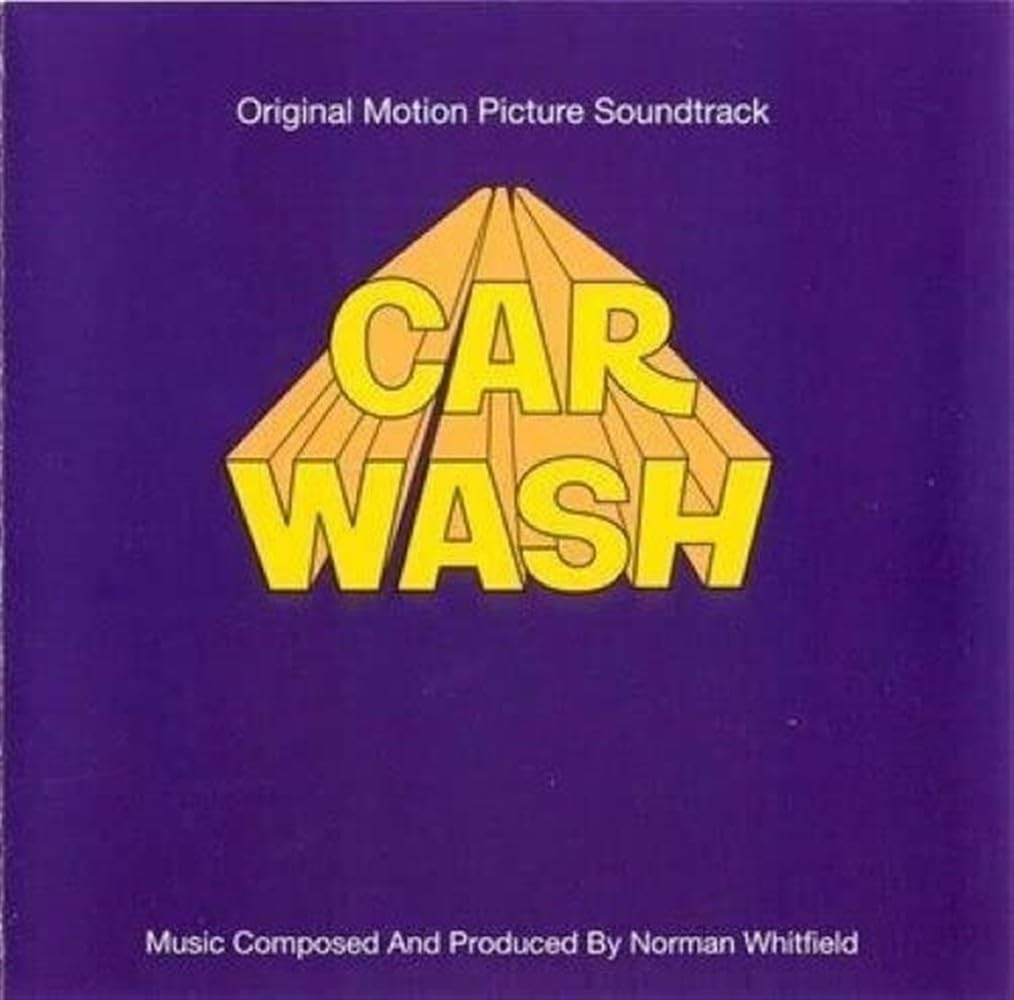

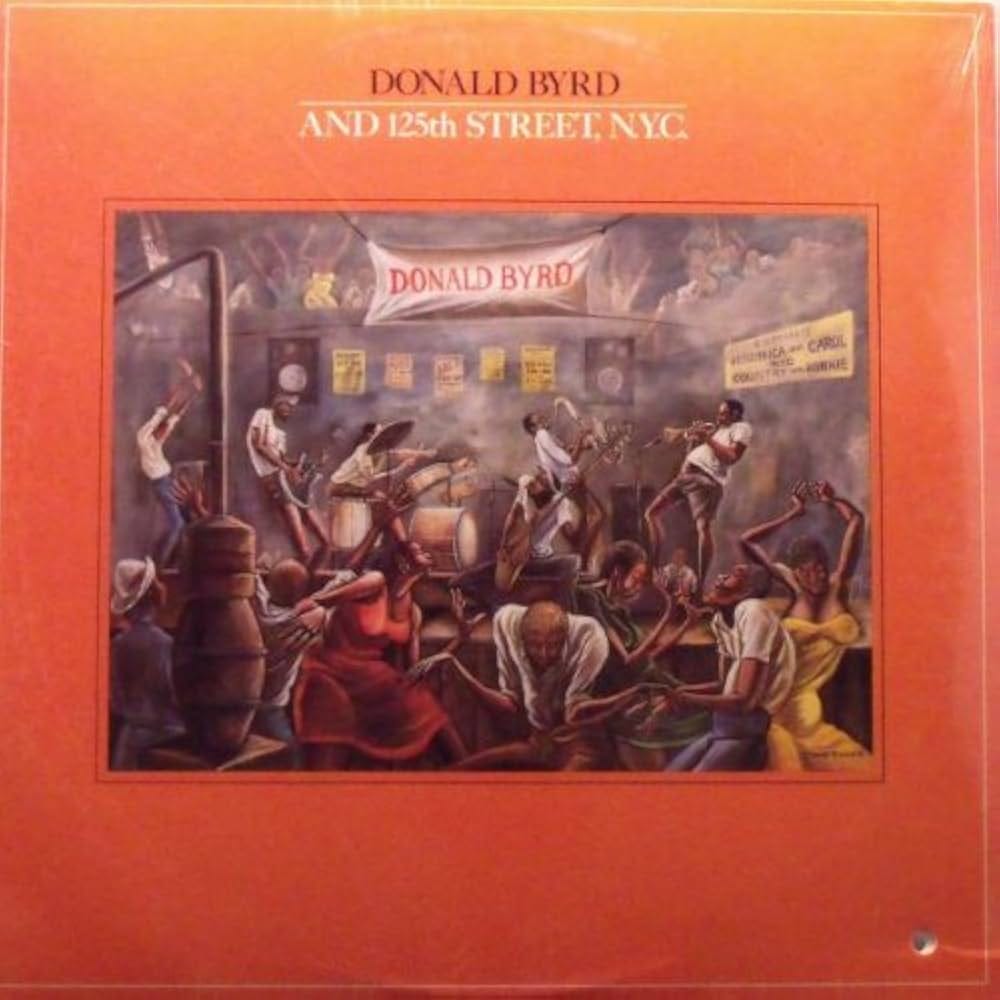

This was the first in a series of funk, soul, and jazz records to feature Ernie’s work over the next decade. Following are just a few of his credits:

Rose Royce—Car Wash Original Motion Picture Soundtrack (1976)

Donald Byrd and 125th Street, N.Y.C.—Donald Byrd and 125th Street, N.Y.C. (1979)

Curtis Mayfield—Something to Believe In (1980)

Crusaders—Ghetto Blaster (1984)

In reality, his reputation as an artist is long and illustrious–far more extensive and meaningful than his impact either on football or popular music. But this mainstream visibility also contributed to one of Ernie’s most redemptive moments.

As the story goes, in 1955, an 18-year-old Ernie Barnes visited the recently desegregated North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh. He asked a museum curator where he could find "paintings by Negro artists".

He was told that, "Your people don't express themselves that way.”

In 1979, Barnes returned to the same museum for a celebrated solo exhibition of his own work.

When Barnes passed away at age 70 in 2009, he left behind an enormous legacy, and is recognized as the leading light of a movement dubbed Black Romanticism. His paintings were highly sought after during his lifetime, and he was paid handsomely for his work.

But there is one painting that Barnes refused to part with, even declining to sell 1965’s The Bench for a purported $25,000 during his first exhibition. Following his death, Ernie’s widow presented the painting to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, where it hangs today.

That’s a great post. Thanks.